Light

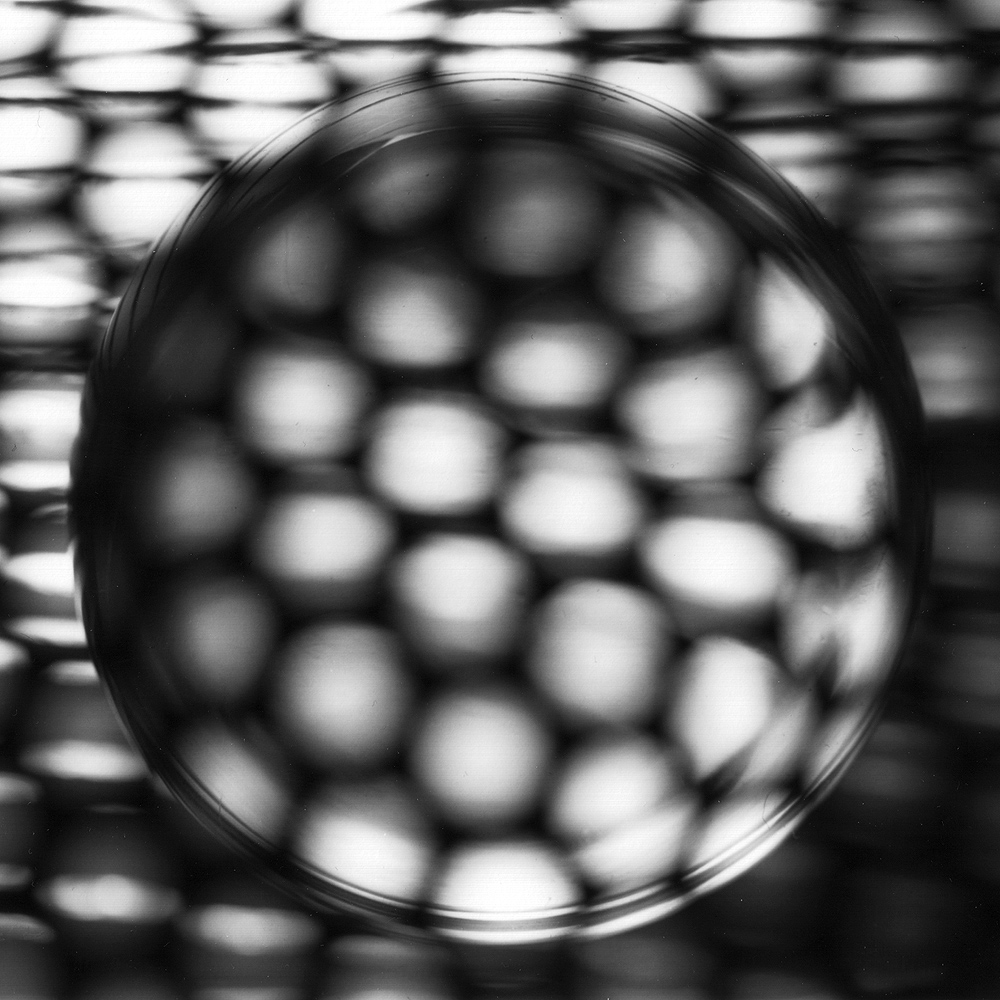

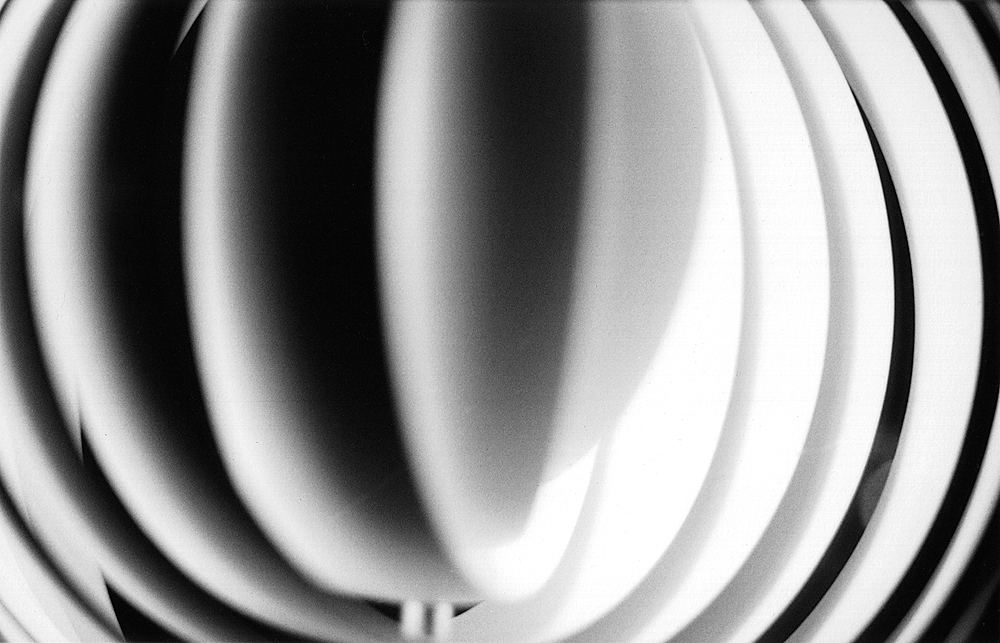

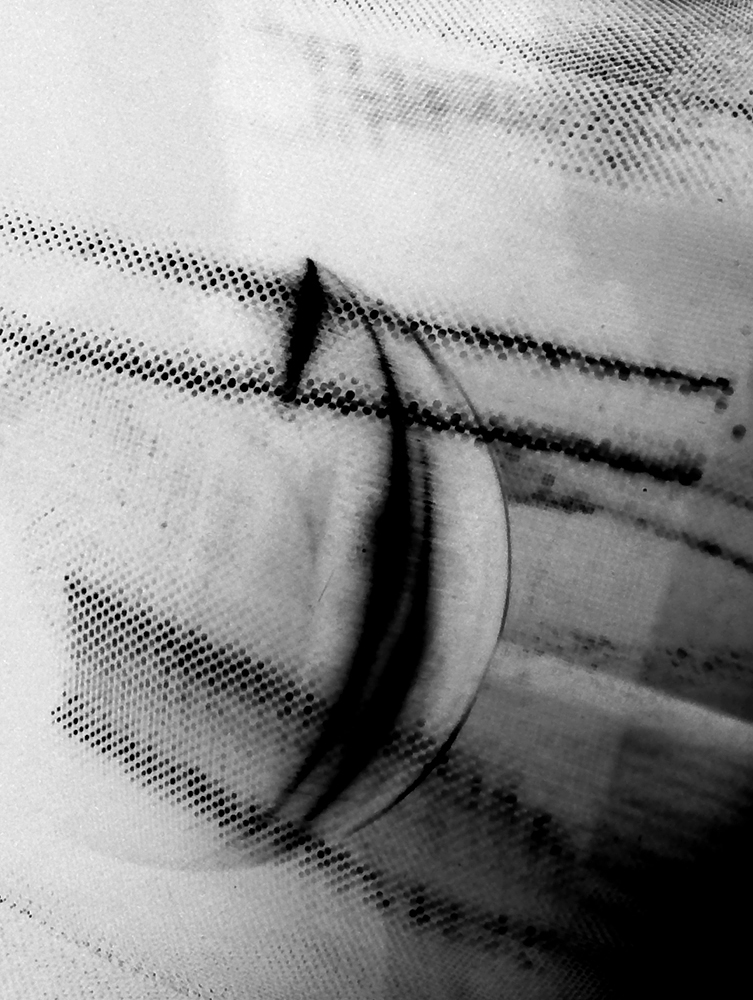

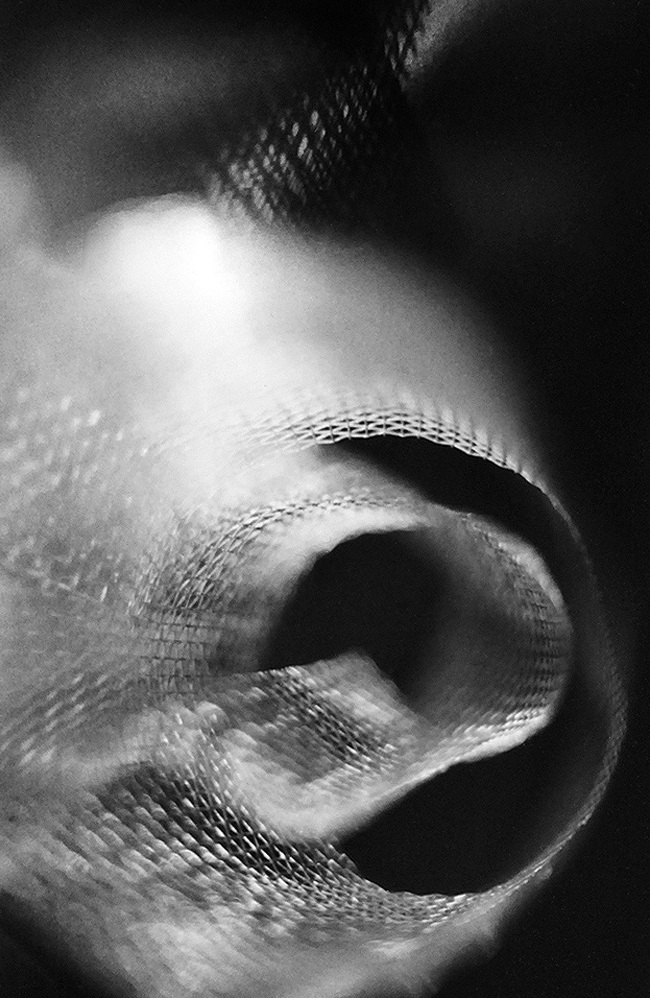

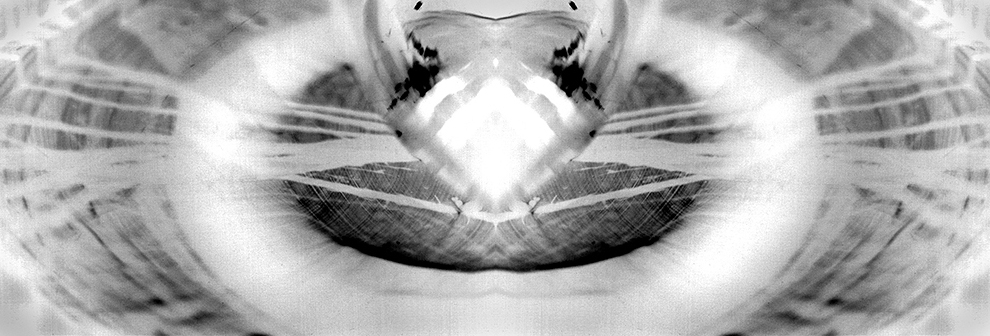

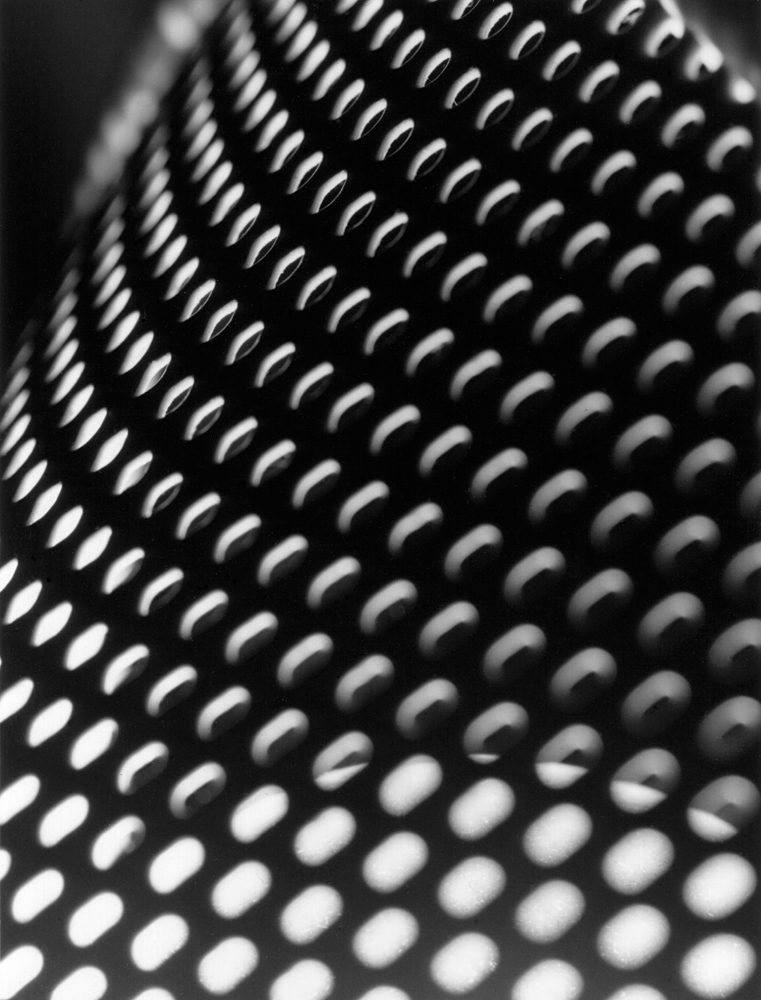

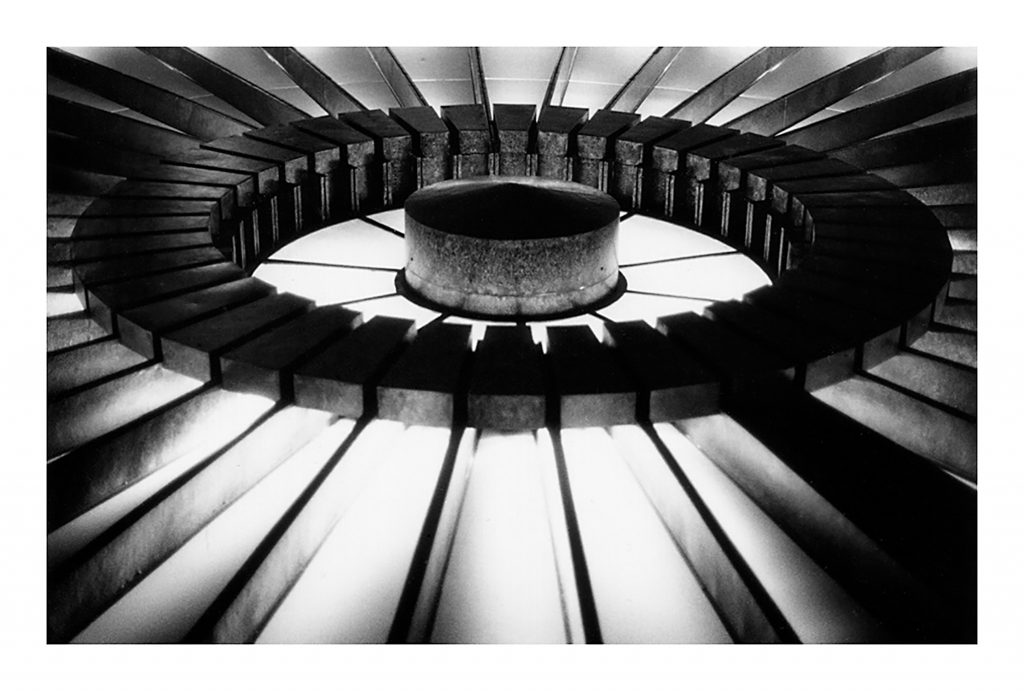

In this series I find myself taking pictures of light itself, using objects to capture the play of light and shadow and the visual rhythm between these two siblings, the sometimes faded border between them, their reflections, opacities. Play is essential to my practice. I am continually falling in love with shapes, forms, beautifully broken things by following patterns and forms that the mysterious phenomenon of light inevitably draws.

The Mysterious Anatomy of Light

— text by Réka Kovács —

In an era of photographic art when analogue, B&W, abstract, and experimental became privileges by themselves and also got devalued as millions of hashtags suggesting the hint of uniqueness in a flood of ordinariness, the series by Csilla Szabó are truly unique.

They are analogue, B&W, abstract and experimental at the same time, so they could be easily associated with a direct line of descent from the Avant-garde or some kind of ‘Neueres’ Sehen. However, they are far from photograms and are lacking in essence-seeking, radical simplification, or the intention to catalog the world.

They are puzzling because the visions they deliver are rather familiar yet still not recognizable. They push us immediately to the borders of our comfort zones, both sights and minds challenged. By taking a little risk to cross the line, we can find ourselves in unlimited play, where participants are free to let stimuli in according to their own state of sensitivity. And so, behind the modest titles like Minutiae, Gleam, Haze, Streak, Meanwhile, or Still, individual universes can unfold.

The precision Szabó handles her medium with in the technical sense is coupled with true effortlessness. As a master of analogue printing, she possesses a wide repertoire of physical tools and alternative processes to study the anatomy of light, and her routine completely misses digital image-capturing and digital manipulation. Her analysis begins with the modification of scale, she examines materiality with black and white methods, and through abstraction, she dissociates conventional readings.

35 mm format snapshots taken with a Canon A-1 are spontaneous records of ready-made findings on the streets or momentary coincidences, while in the case of the large format Linhof Technika, exposure can take days from the first glimpse into the viewfinder.

In the development phase, in the ‘silver mine’ as Szabó refers to her practice, her proficiency provides a good basis for experiments and also – fun. The process that started with the chance of finding the original objects here enters the stage of mindful, scientific attention, where each line, blur, and chemical reaction have their role, and together they lead to the discovery. Once everything takes its place inside the structure of the image, the event is verified by an intense, personal emotional response. The unknown component, being there the whole time, reveals itself only in this fragile moment, glared and pervaded by the evoked feelings.

The richness in detail sometimes indicates the dimensions of microscope slides, converting meticulousness into closeness in a specific way. None of the subjects are of microscopic scale, though. When enlarging their details, the point is rather the freely chosen ratio and the impulse behind the artist’s interest. The way how some prosaic, filched, coincidentally spotted, tiny baubles turn into exceptional moments of light.

This unusual approach – analogue, B&W, abstract, experimental, meticulous, easy – seems to be hard to find a match of. Actually, some representatives of the Eastern European avant-garde can be mentioned as parallel examples, but only tangentially, because only a few criteria are similar. The elements in the Czech artist Jaroslav Rössler’s light compositions, for instance, are usually recognizable: several angles of the same apple in the same image, or a self-portrait hidden amongst abstract shapes. The Croatian painter Antun Motika’s experimental light paintings or his installations designed for slide-projectors or overhead projectors are obviously not photos. But with all the beetle legs, buttons, petals, or random colored paint splatters involved, they give a new, extraordinary context to the big and significant in the tiny.

Běla Kolářová was the one who endowed banal with a new significance through photography and alternative methods, refusing the idea that everything had been photographed. Her abstract photograms made in the ’60s, then her assemblages analyzing, systematizing, moreover fetishizing the most everyday objects, concentrated on their original quality, vision, and function. By the manyness shown, these works depict a new dimension, and also psychological and social contexts.

For Csilla Szabó, neither the original functions or sizes nor social or psychological aspects of the subjects are relevant. She especially avoids particular meanings forced on them. Her focus is on the experience and emotions triggered by the discovered composition. The artist and perceiver’s sides of the creative process are both terrains for intuition. They are spaces where childlike, instinctive reactions resonate through from the time of exploring the physical world.

The traceable, credible technical methods (much like science) result in the perfect moment emerging from the infinity of possible pictures, like a random shape inside a kaleidoscope. Szabó’s individual impression filters and fixes it on her side, while on the observer’s side, a lifetime of personal knowledge and patterns will come into play.

What else would this be than the art of writing with light itself? Photography itself, and even one subtle instant beyond its own self? Condensation and expansion of time, getting close, drawing back, focus, depth – the elaborate care and precise research concentrated in the images open the way for further connections, and give something even when we look at them for half a second, even when for half an hour.

Everything is free and unconstrained, and above all, it is about the soul of the observer. As much as we are ready to indulge in receiving, unknown territories may open without words. But it is still alright to guess, to talk, to play, or to recoil: the kaleidoscope turns around, the refraction flickers, all variable and diverse.

These many little personalized worlds manifest on the newest platforms of photography as well, in the online superabundance of everyday life documented inch by inch. We report ourselves, our things, our topics, and we keep searching on and on, then we scroll through archetypes, technical achievements, filters, Tetris challenges, and microcosms without a glimpse. Because there is nothing new, yet everything is unrepeatable because everything is our very own, and yet absolutely common.

The analogue images by Csilla Szabó that we encounter in real time and actual size are independently valid and complete but are also connected in infinite variations. They are able to stop the cycle for a perfect moment, in constant change, in a strange manner or familiarly, to enlighten us by the inexhaustible richness of responses that can be given to them.

___

Matthew S. Witkovsky (2013): Thought Patterns. In: Běla Kolářová, exhibition catalogue, Raven Row, London, 45-55.

Marie Klimešová (2016): Jiří Kolář and Běla Kolářová’s Permeable Universes.

In: Jiří Kolář – Běla Kolářová, exhibition catalogue, Vintage Galéria, Budapest.