Fish

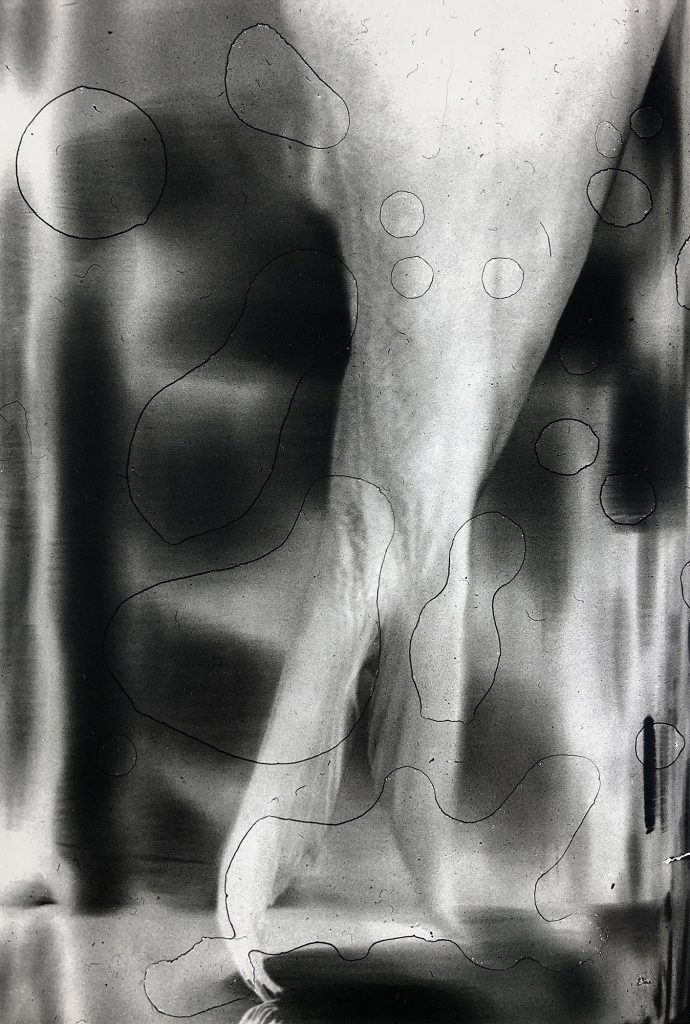

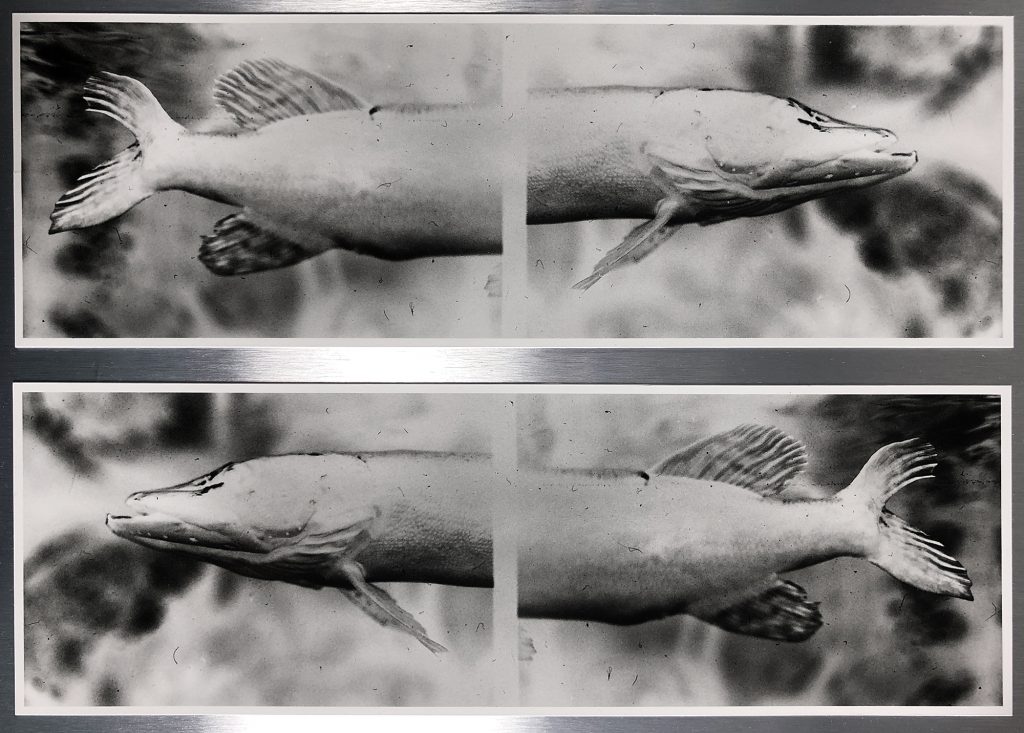

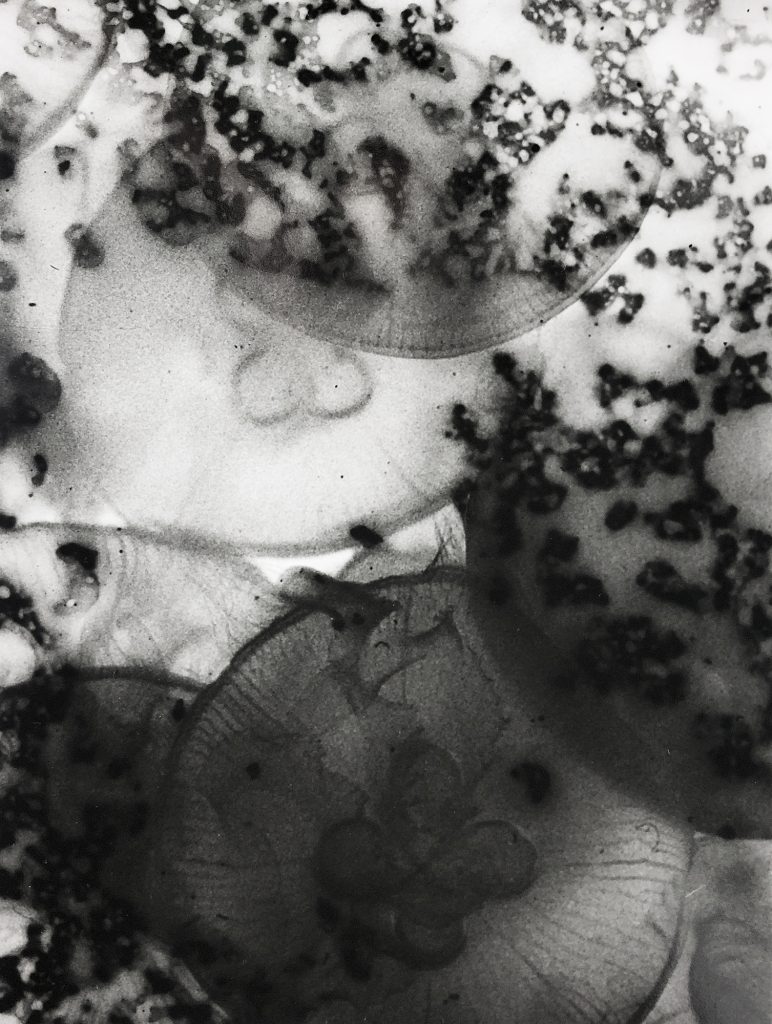

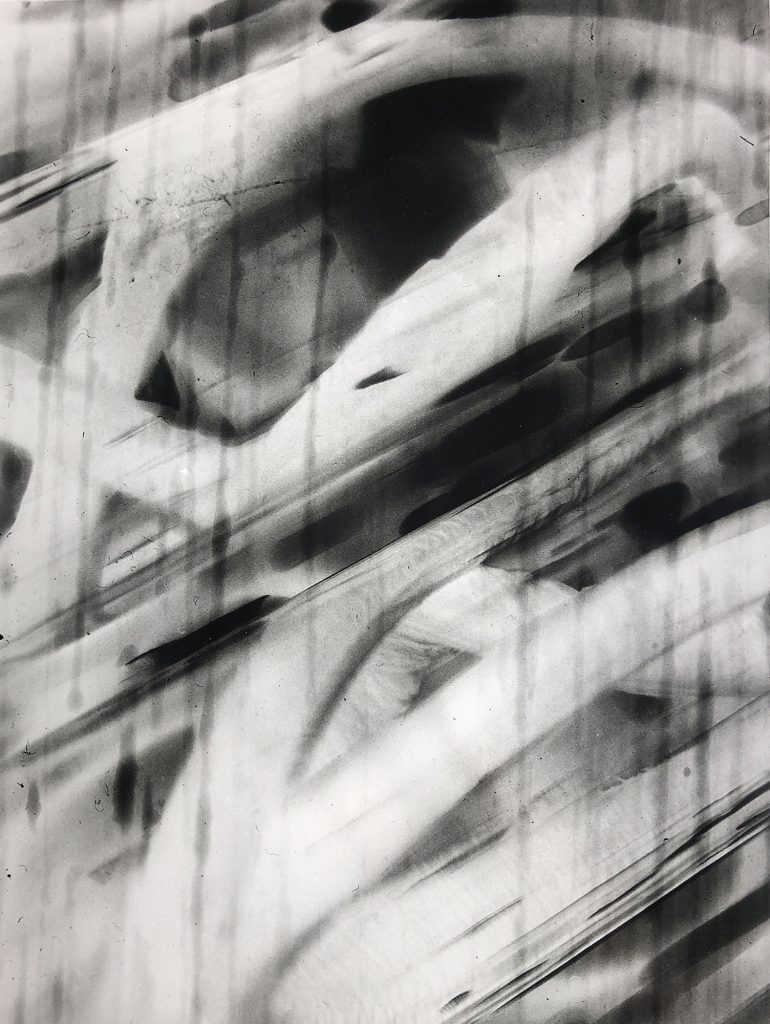

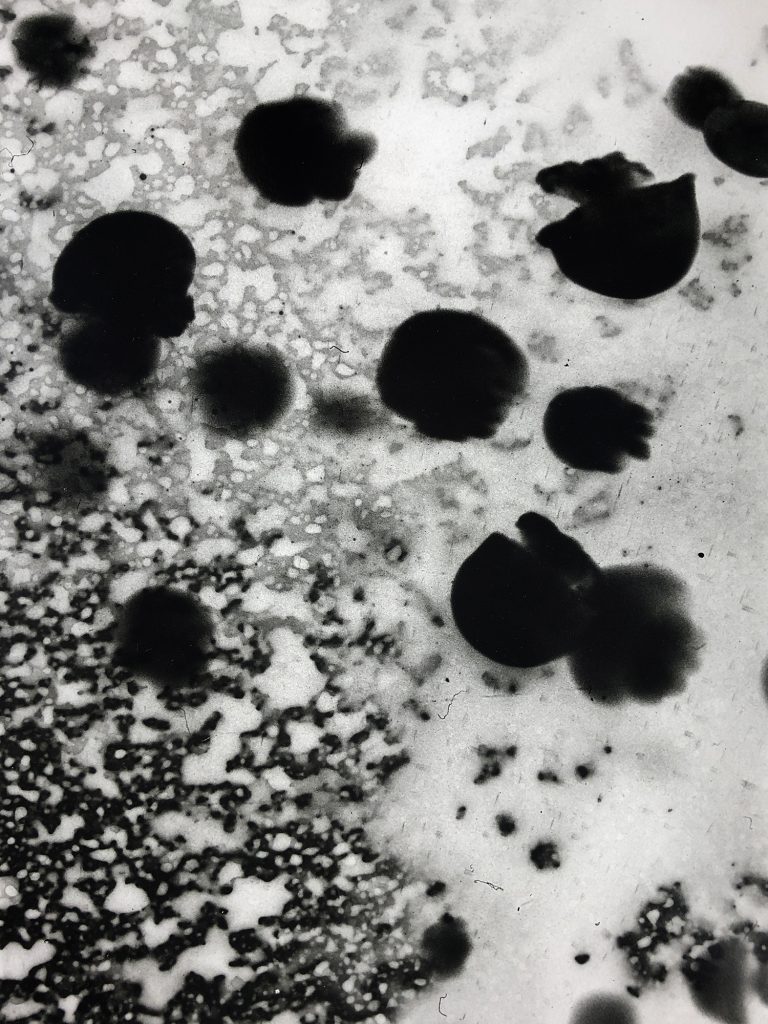

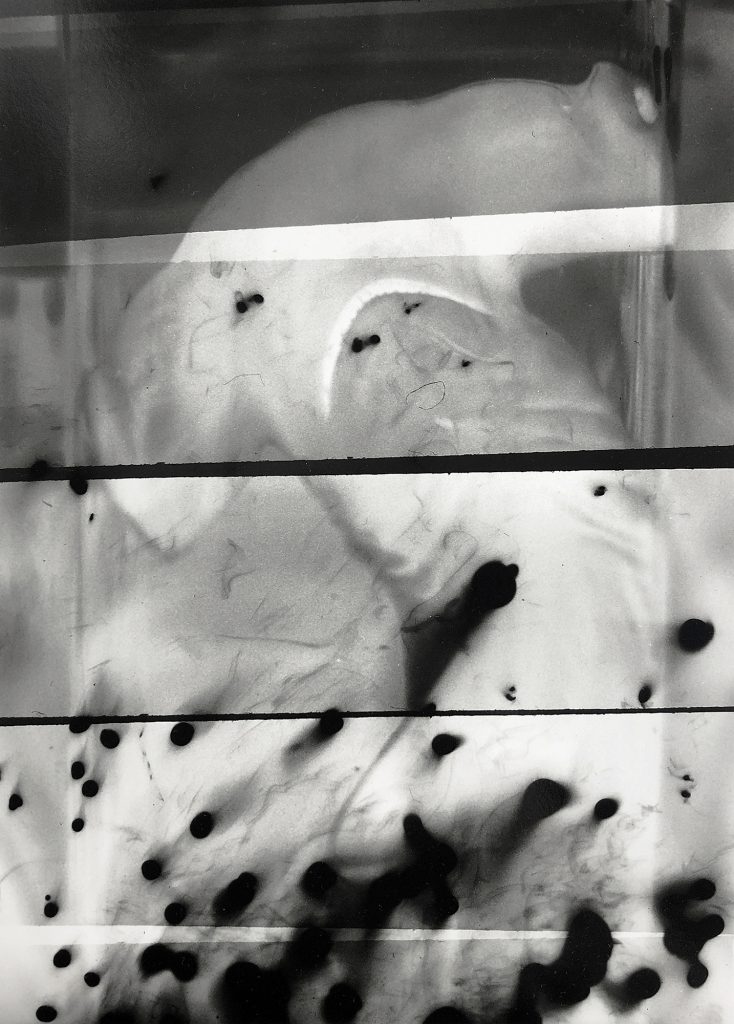

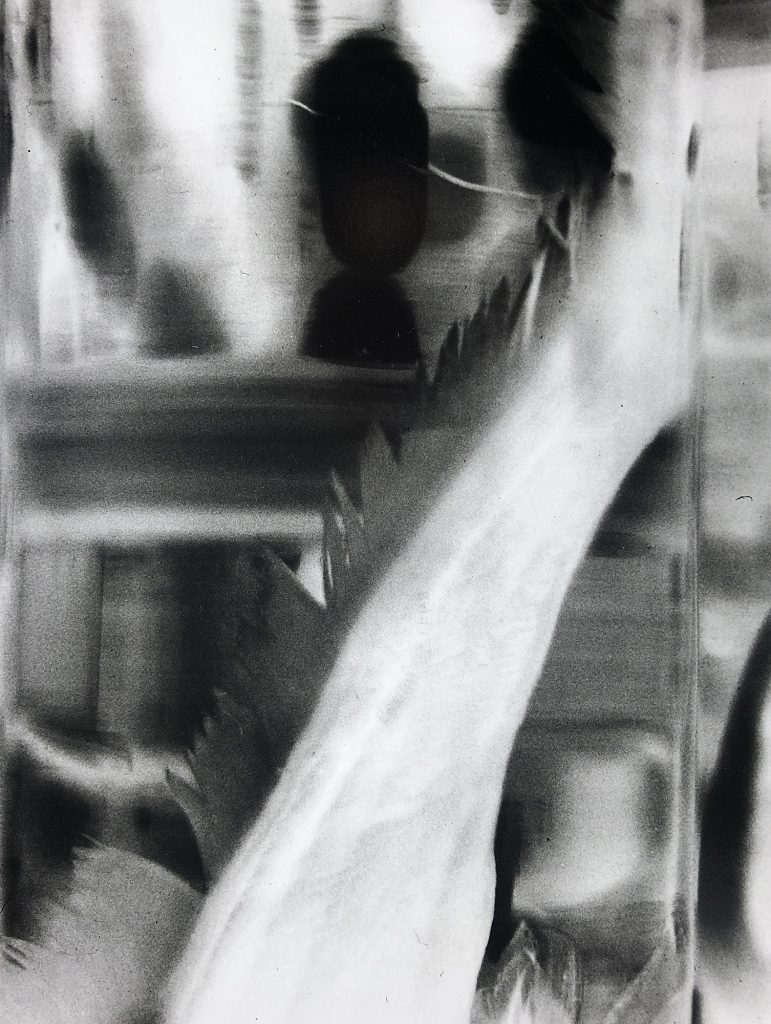

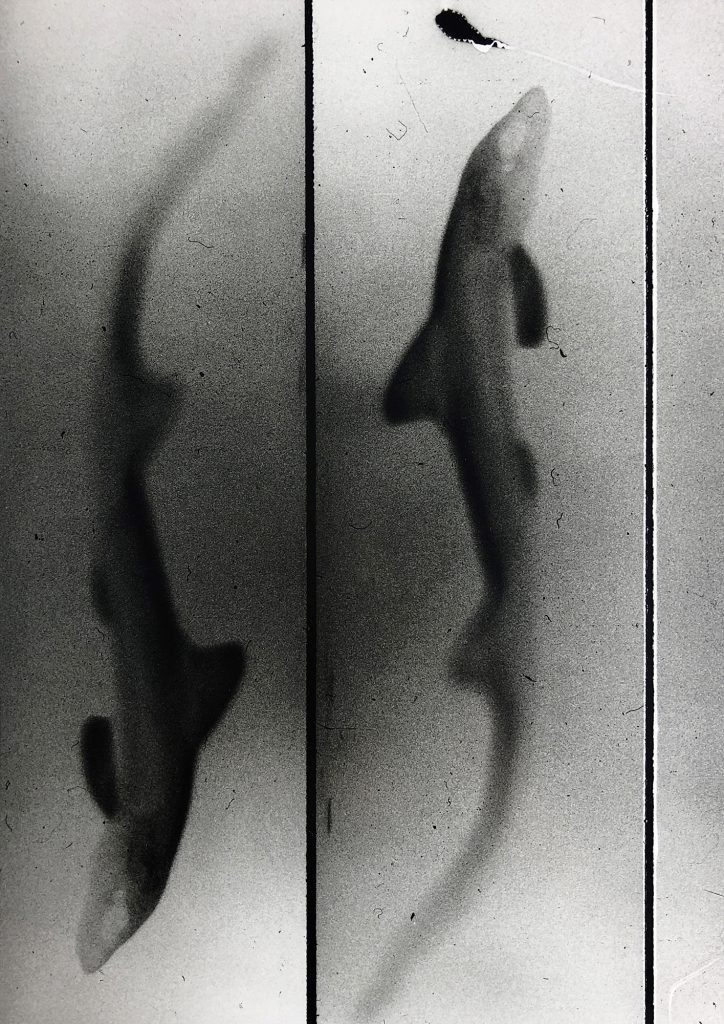

An analog photographic series depicting different water creatures. The photographs have been heavily modified in the darkroom with different chemical and physical techniques.

The monochrome domain, the analog photographic methods, the different handcrafting techniques and the manual manipulations are all defining elements. Like the alchemist in her den, I abstract reality. In this series I enlarged and magically transformed sea creatures into demonic totems.

The models I have found in zoos, museums, markets and sometimes on the kitchen counter. Photographing them was only the initial step, the real creative work happened in my darkroom. Through numerous steps I have pealed off the realistic elements of these animals and washed away their naturalistic traits. Play and chance are essential in my personal practice, as opposed to the controlled environment in my commissioned printing work. I am continuously pushing the boundaries of traditional silver gelatin printing.

While fishing for the secrets of the Deep in the amber light, these mythological, demonic totems are emerging from my darkroom trays, swimming into the light, whispering to the unconscious. Through this creative voyage I explore the hidden, spiritual world that humanity tries to comprehend for thousands of years.

A pond of Unconscious

– text by Réka Kovács –

When someone chooses aquatic organisms as subjects, the audience can easily associate them with hot topics like the endangered ecosystem, sustainable food production, or with many universal references like Christian iconography, or the world of ancient myths and symbols – or even an outrageously overpriced carcass of a shark.

But Csilla Szabó dives into a more primary territory than these connections, taking us with her. Similarly to her works in Demonography or The Mysterious Anatomy of Light series, her interest turns to details and freely unfolding stories, with the important difference that in the case of fish, clearly recognizable elements appear.

Figurativeness, however, doesn’t mean a documentarian approach.

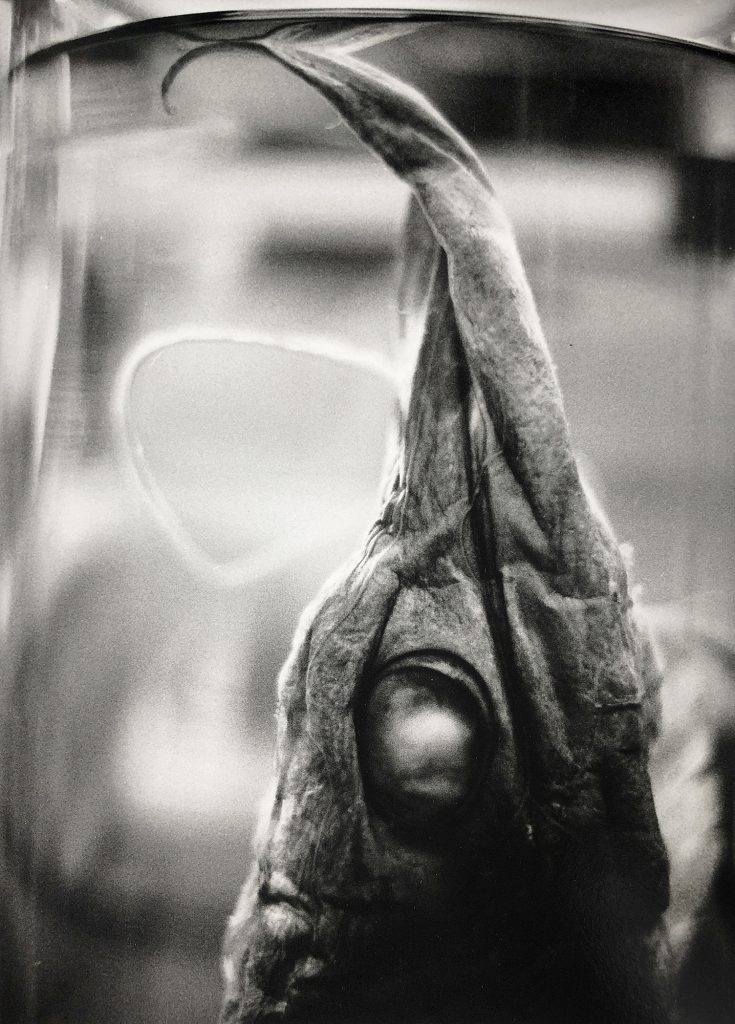

Let them be living or dead, bizarre giants exhibited in an aquarium, bodies writhing in the fish market, the dinner being prepared on a kitchen counter or zoological specimens preserved in fluid, the gripping unearthliness of fish and other aquatic life forms, even deformed or decayed, attracts the gaze. The featured details still can be puzzling, just like the Demons. We don’t know if it is a head or a tail, a giant mouth, a tooth, a tentacle, or an eye that we see, yet they trigger a set of visceral reflexes.

Fish carcasses are also recurring characters in Brett Weston‘s oeuvre. The fish market catch, the jellyfish thrown ashore, the puddles left at low tide, the semi vegetal and semi animal formulas of seaweed are impressive, but his interest is mainly of a formal nature. While a few of his abstract works are reminiscent of fins or even shark teeth, his strong contrasts, the richness of surfaces presented by him are rather pieces of evidence of material existence.

In Csilla Szabó’s non-realism, composition is prime, but in this case, besides holding to recognizability, we see the gradual fade-out of materiality. During the development, Szabó plays around with the animal body parts as if they were abstract forms, but she does not reconstruct or animate them. The process is exactly the opposite of the birth of the monsters of Demonography.

The first step of creative work, which can be interpreted as an analogy of catching fish, is always capturing the negative image, snapping visions purposefully sought and found in aquariums, scientific collections, or at fish counters. During the fully manual photographic process, of which Szabó is an internationally recognized master, the processing baths turn into fish graders and the darkroom itself into a ritual scene.

By the magic of reverse-processing, dipping, cutting, scratching, and different collage techniques, the characters in the prints sometimes seem to be caught in nets, or the dynamics of water get perceptible by splatters and multiplications. These are the traces of a living habitat in the lab, but this ain’t no National Geographic. The gaze of the vigilantly observing artist, who carries out the multi-stage manipulation, sometimes only wanders into the dimension beyond the bodies, then consciously remains and seeks further in the realm where the hidden, mythical nature of the beings can surface and where they transubstantiate into icons.

Their sliminess disappears like that of the fish of the traditional Japanese printmaking method gyotaku, during which the skin is carefully cleaned so that the ink adheres well to it. A perfect print gets onto the surface of the washi then; just as the flounders and sardines spread out to dry in Weston’s Japanese photographs are as sharp as lithographs. The aim is to prove the size of the prey or to give a sensual presentation of the fleeting material by abstraction or by highlighting characteristic features.

Instead of an idealized or overdone aesthetic, Szabó communicates with another nature. The axially mirrored, geometrically arranged, or radiating bodies begin to function as totems: the photo paper soaked in the developer, then rinsed, is the medium through which the hunter gets into touch with another world.

Fish 4, 70 x 100 cm, Silver Gelatin Print, Edition of 7 © Csilla Szabo Photography

Water is a closed territory for humans, and the encounter of elements is inherently exciting. The ancient activity of fishing has shaped human culture from the beginning: spirituality, physical kinship, and divine presence are living bonds between man and animal. The meditative attention of a night angler, a shaman entering the trance state for successful fishing, a sailor telling stories of imaginary monsters – just as the photographer making her prints, they all scan secrets of the deep.

When the creatures emerge from it, by the symbolic abilities assigned to them, fulfill their mission. Embodying intuition, these fertile, instinct-driven things rely on currents to guide us through the water, the realm of the ancient beginning, death, and renewal.

The artistic intervention, which makes the black lines running through the bodies of the fish look like bamboo protruding from the water, seems to be the activity of the subconscious. Fishing with nets affixed to such stakes was a common practice across Asia, also documented by Weston. Or would the Asian parallels be only the viewer’s associations? And what about the biblical story of the multiplied fish? Like in other series by Szabó, interpretation is free and doesn’t depend on cultural spheres. But such hints suggest a common basis for fish bodies to become icons, that is the same in all of us: the deep connection to each other, as physical and spiritual beings.

The Danish glass artist Steffen Dam also intends to stimulate imagination and hold a mirror to the soul by water, or rather precisely its imitation, and fictional sea creatures. His organic forms placed in containers by the concept of Wunderkammers are as strange and familiar as the subjects of Szabó’s meticulous search.

As the creatures of fantasy are frozen in glass, the fish spirits preserved with the fixer, instead of formalin, can be observed for long, and they can show something new at any time. By dipping the photo paper, Szabó allows them to convey the messages of the closed dimension as photographic signs.

All this makes a special extra sense if we take the primary meaning of the word előhívás (‘calling something forth’) used for development in her mother tongue, Hungarian. As if she was actually calling memories, impressions, feelings, and beings, inhabiting the big sea with her fishing lamp forth, so they show up in the trays of the darkroom.

She makes their evanescent, unfathomable image stay in the upper world so that we can reconnect with our primordial experiences when looking at them.